Partagez vos expériences ou souvenirs!

- Vous avez dansé Mozongi?

- Vous avez aimé Mozongi?

- Vous voulez partager vos expériences ou vos souvenirs?

La boîte ouverte accueille vos textes, vos dessins ou vos images libres de droits autour de Mozongi.

Envoyez votre témoignage à info@espaceperreault.ca.

La mémoire étant une faculté parfois créative, Espace Perreault n’est pas responsable de l’exactitude des textes déposés, mais ne diffusera que les propos respectueux.

À vos plumes!

Share your experiences or memories!

- Did you dance Mozongi?

- Did you like Mozongi?

- Would you like to share your experiences or memories?

The Open Toolkit welcomes your texts, drawings or royalty-free images about Mozongi.

Send your story to info@espaceperreault.ca.

As memory is sometimes a creative faculty, Espace Perreault is not responsible for the accuracy of the texts submitted, but will only distribute respectful comments.

Get writing!

Comme un mirage - Marie-Claude Gervais (danseuse de Mozongi en 2001)

Mozongi représente pour moi un passage dans le temps. Je nous revois toutes les quatre [avec Karla Etienne, Marion Landers et Claudine Malard] entrant sur scène, couchées sur le dos, en train de reculer, sur les tambours. En rampant à reculons, j’avais l’impression de revenir dans le temps. Cette pièce a traversé mon corps comme une mémoire du mouvement. Physiquement, j’ai des souvenirs de mouvements qui me reviennent, des sons qu’on faisait – le travail du souffle était particulièrement épuisant et exigeant – et j’ai des flashs de rythmes. C’est comme un mirage.

À l’époque, j’aimais beaucoup la danse africaine. À New York où j’ai vécu plusieurs années, j’explorais des courants issus de la Guinée Conakry, de la Côte d’Ivoire et du Sabar du Sénégal. J’ai découvert ces approches africaines tandis que je m’entraînais en modern jazz dans le studio de Lynn Simonson. Mais quand les compagnies de danse ont commencé à utiliser les courants afro à la sauce contemporaine, j’ai trouvé ça dichotomique. En revanche, le travail que Zab a développé en Amérique du Nord proposait un mariage parfait entre le vocabulaire traditionnel et ses influences contemporaines à travers un vocabulaire distinct de ceux que j’avais connus à New York. J’ai adoré la façon dont elle réussissait à transformer les structures. Je suis heureuse d’avoir dansé de l’Africain à Montréal même si l’expérience fut difficile.

Mozongi est une chorégraphie physiquement très exigeante et c’était tout un défi de travailler avec une chorégraphe au langage si précis. Il nous fallait assimiler la façon dont Zab aborde ses mouvements, avec ma longueur de bras, le rythme, le volume du corps, l’énergie que je pouvais transmettre. Pour chacune d’entre nous, c’était très différent, surtout pour moi qui suis grande! Zab me reprenait constamment sur ma façon de sauter. Le rebond du mouvement n’était jamais à la bonne place. L’expérience était à la fois éprouvante et jouissive.

Nous étions habitées par ce langage qui venait d’ailleurs et qui est ancestral. Il s’agissait de mouvements très organiques tels que ramper au sol comme un serpent, puis marcher assises par terre et, enfin, se redresser et danser debout… La construction chorégraphique en crescendo correspondait aux étapes de grandir. Telle la marche de l’humain, ce travail structuré vient chercher nos gênes. Nous étions des canaux. C’est à cette époque-là que j’ai compris ce que danser signifier. J’étais un véhicule et Mozongi passait à travers moi. Alors que je croyais que les mouvements étaient instinctifs et nous provenaient de l’intérieur, je sentais dans ce cas-ci qu’il s’agissait d’un langage, d’un vocabulaire, des phrases, d’une chanson, d’une histoire qui existent en dehors de moi. J’étais un canal à travers lequel s’exprimait physiquement une histoire. C’est ça la danse. C’est ce qui donne le sens du mouvement. C’est l’essence du mouvement!

En tant que danseuses pigistes, nous étions payées pour les performances mais pas pour les répétitions. Même si Zab nous offrait ses classes pour l’entraînement, j’ai fini par lâcher car je trouvais le métier de danseuse physiquement trop exigeant. Nous nous entraînions beaucoup et les mouvements au sol, comme marcher sur les fesses, ont réveillé une blessure antérieure au niveau de l’articulation coxo-fémorale. Ce spectacle me procurait à la fois une source de plaisir et de douleur. Alors que je vivais ma première grande expérience scénique en danse contemporaine, j’étais à un carrefour de ma vie. J’ai ainsi mis la danse de côté pour me consacrer au yoga, en tant qu’art de guérison. Cet aspect a prévalu tout au long de mon parcours à travers la massothérapie et le yoga que j’enseigne encore aujourd’hui.

J’avais suivi une formation en ballet dès l’âge de 14 ans avec Eddie Toussaint que j’ai dû abandonner à 17 ans en raison d’une blessure à la cheville. À l’adolescence, je ne savais pas encore comment travailler adéquatement mon corps et les maîtres de ballet changeait trop souvent pour être en mesure de connaître nos limites. Je me suis blessée en pensant le problème venait de la cheville. Mes notions en massothérapie m’ont permis de comprendre plus tard que ma blessure résultait d’un problème à la hanche. Ce fut extrêmement difficile pour moi d’arrêter de danser alors je me suis dit : « Si je ne peux plus danser, je vais guérir les danseurs. » C’est l’histoire de ma vie et c’est ce que la massothérapie m’a apportée.

À 25 ans, j’ai été sélectionnée pour étudier un mois au Jacob Pillow Dance Festival grâce à une bourse de General Electric Canada. Comme j’avais toujours mal au pied, j’ai consulté un massothérapeute sur place et ma douleur a disparu. Je m’entraînais huit heures par jour, six jours sur sept, en ballet, en contemporain et en jazz avec Lynn Simonson et je n’avais plus mal au pied! Alors à la fin du stage, je me suis dit : « C’est maintenant que ça se passe! Je m’en vais vivre à New York! » Je devais me remettre en forme car j’avais arrêté de danser depuis dix ans. J’ai suivi Lynn à New York qui développait une nouvelle approche qui s’appelait « New Vision for Dance » et qui intégrait le yoga pour préparer le corps de manière holistique, rester en forme et danser le plus longtemps possible. J’ai obtenu des contrats pour le Japon et Monaco et j’ai également été mannequin. Au bout de trois ans, je suis partie en France pour un diplôme d’État en enseignement en danse jazz. Je m’entraînais encore avec Lynn qui donnait des stages à Paris. Je suis revenue à Montréal fin 1997 pour commencer une formation de yoga Iyengar. Je suivais des cours à Nyata Nyata au-dessus du Balatou et Zab m’a proposé de danser Mozongi en 2001.

Mozongi fait partie de moi, je ne peux pas m’en défaire. La danse est toujours ancrée en moi. Il y avait un mouvement très sinueux que j’adorais. J’entends encore notre souffle! Comme si on partait en transe. Ce mouvement qu’on appelait « Mozongi » arrivait vers la fin alors qu’on était fatiguées… C’était transcendant! Les larmes me viennent quand j’y repense! Ce mouvement de l’ondulation, tout comme les mouvements de balancier assis par terre, me collent à la peau. Je me rappelle que j’avais un plaisir fou à les danser! Comme un jeu d’enfant, ça allait avec une forme de bien-être et mon goût du rythme hérité de mon père qui est jazzman.

Mozongi a laissé une trace indélébile qui correspond à un tournant de ma vie. Quand je masse, la danse est toujours présente, parce que je me connecte à l’énergie et au mouvement. C’est ce qui fait que je masse encore après quarante ans, alors que certaines personnes se brûlent au bout de cinq ans car elles ne travaillent qu’avec les mains, alors qu’il faut travailler avec son corps, avec le poids, avec le rythme.

Deep listening - By George Stamos

Ta-ka-tum-ta-ta-te-TUM-tum-ta-ka-tum-ta-ka-tum !… Mozongi has many, but one prominant rhythm I remember. Ta-ka-tum-ta-ta-te-TUM-tum-ta-ka-tum-ta-ka-tum !… It’s also a footwork. The “tum” is a foot on the ground. And then, there’s a little flight: “te-ta-te-ta-ta-ta”. It’s a very elementary work that is inscribed both in the ground, the body and in the air, all as one. When I think of Mozongi, I think of the deepest part of the earth to produce energy. These rhythms persist and remain anchored in me, like a heartbeat that will remain throughout my life.

Ta-ka-tum-ta-ta-te-TUM-tum-ta-ka-tum-ta-ka-tum !…

I danced Mozongi after Montreal by night, to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Nyata Nyata company in 2014. This piece represented a great challenge for me in terms of a type of floor work that was very challenging. The challenge was about not compressing my body even while going deeper into the anchoring with the lo (of the lokéto) and the levels. I had danced the piece once and when Zab was looking for dancers to remount the work again for a tour, I told Zab that Mozongi concerns “those who come back”, and not “those who leave”, and that she should therefore take me back, and we laughed. I thus returned to the company in 2016-2017 for a tour of Mozongi across Canada.

Zab is a philosopher, a master, with whom you always engage in a stimulating conversation. That is what attracted me to her, as a person as well as an artist and teacher. I met her at a showcase at Place des Arts, then on a CALQ jury. We had our own perspectives, and shared a lot of points of view, in addition to living in the same neighborhood! When there were auditions for her company, I showed up with only a little background in African dance because she inspired me as a dancer. In working with Zab, I came to realize that some types of dance from Afro-descendant cultures and movements had been ingrained in my body since my youth, especially through club dancing, but I still had a great deal to learn about the technique and cultural significance of this liniage, but at least I was good enough for Zab to hire me.

So I trained at her school about 12 hours of class time per week and worked in her company before and after classes. I felt that I could fully support Zab’s work as a dancer and it was very enriching because, after fifteen years of career in contemporary dance as a performer and choreographer in Montreal, I was bored. The dancer’s job is to support the artistic project whatever it is and as best you can. But I no longer felt I could honestly support part of the work I was collaborating on with some companies! Had I become too old to be a dancer? What bored me is that between the choreographer and the dancer, there was a parent/adolescent relationship that, in the late thirties, did not feel like a healthy or authentic relationship.

Ta-ka-tum-ta-ta-te-TUM-tum-ta-ka-tum-ta-ka-tum !… This rhythm is present at the end of the piece but runs through several sections with variations. I have not danced this piece for years, but this rhythm has never left me. It is surely the one I had to work on the most. We spent a lot of time on this one. It is the theme of the piece. It requires maintaining such anchoring and such lightness that it requires both a lot of listening and a constant maintenance of openness. It is not only an expression, nor a liberation, but deep listening.

In dancing the work, at the end of the piece, something was released my the body I felt a space open up on a metaphysical and physical level, a kind of liquid that flows as if you had dug so deep that you reached the lava or the core. There is a warmth… It seems like a fusion that you could call a release. I felt like I could hum the choreography when until then, I had the feeling of having to calm my body down to inform it that I was not having a cardiac arrest! Your heart starts beating so fast! Accessing a lightness with precision and anchoring is a real pleasure as an experience, as a person and in terms of sensation. I was able to use this solid technique that Zab shares to survive the piece and I am so thankful for her teachings and the time I spent dancing in her work.

George Stamos, Bruno Martinez, Karla Etienne, Luis Cabanzo, Elli Miller-Maboungou, Mithra Rabel à Dorval. Photographe inconnu.e, 2016

Pèlerinage - Thiery Liverpol (danseur de Mozongi en 1999)

Dans ma recherche dans les archives de Mozongi, Thierry Liverpol se présente comme un véritable « revenant »! En effet, dans les archives, nulle trace de son nom, ni de son passage dans la pièce. Et pourtant, il fut de la distribution. Vingt-cinq ans plus tard, il se souvient avec précision des pas et de la chorégraphie. Je l’ai rencontré lors de son passage à Montréal à l’été 2024 alors que je finalisais la boîte chorégraphique. Depuis, je l’ai retrouvé sur quelques photos d’archives. J’ai profité de son « pèlerinage » à Montréal afin d’enregistrer son témoignage pour la version numérique de la boîte chorégraphique. Je n’ai encore jamais croisé quelqu'un qui ne m'a pas raconté un récit extraordinaire en lien avec cette pièce. – Katya Montaignac

Dans mon parcours en danse, mon passage à Nyata Nyata représente un véritable chemin de croix. Ce studio est quasiment un lieu de culte qui accueille beaucoup de pèlerins avec des bagages parfois chargés. En France, j’ai suivi une formation plutôt hiérarchique dans un cadre très triangulaire, d’abord avec la danse jazz, puis le ballet classique et le contemporain. Or, à Nyata Nyata, je suis entré dans un cercle : il s’agit d’une famille, d’une communauté. J’ai été accueilli comme sur une nouvelle terre. Ce fut compliqué pour moi car il m’a fallu déconstruire de nombreux éléments ancrés dans mon corps comme dans ma pratique de la danse.

Je suis arrivé au Québec par le biais de l’Agence Québec Wallonie Bruxelles pour la Jeunesse (AQWBJ) pour suivre le bac en danse à l’UQAM et j’ai rencontré Zab dans le cadre d’une invitation du département de danse. J’ai été touché par son travail sophistiqué, tant au niveau intellectuel que chorégraphique, ainsi que par son profil atypique en tant que philosophe et pionnière de la danse africaine contemporaine originaire à la fois de France et d’Afrique. Je me souviens avoir vu son solo au Festival international de nouvelle danse (FIND) que la critique du New York Times décrivait comme « un diamant brut ». Je suis donc allé, par curiosité, voir où elle travaillait.

Nyata Nyata est une colonne vertébrale dont Zab Maboungou est le sacrum. Généreuse, philosophe et matriarcale, Zab est une mère nourricière. Elle a une assise et une autorité naturelle avec laquelle il n’est pas toujours évident de composer. Pour ma part, j’ai dû rattraper en trois mois le niveau de danseurs présents depuis six ans! Son écriture chorégraphique me paraît désormais plus accessible : elle est parvenue selon moi à une synthèse pédagogique qui facilite la compréhension de son langage, tout en conservant sa complexité.

Mozongi représente pour moi une sorte de pèlerinage. Nous avons dansé cette pièce en 1998 et 1999 dans les maisons de la culture : je me souviens du Plateau Mont-Royal, de Rivière-des-Prairies, ainsi que d’une représentation spéciale de Mozongi au musée Saydie-Bronfman en lien avec le génocide du Rwanda. Pour l’occasion, Zab avait recouvert la scène de vêtements, c’était magnifique!

Quand tu danses Mozongi, tu entres véritablement en transe. La chorégraphie est complexe mais elle te transcende! On creuse au sens figuré comme au sens propre! On sortait de répétitions de six heures, exténués, parfois durant des nocturnes ou des fins de semaine. Je n’ai jamais autant maigri de ma vie et, paradoxalement, je me sentais puissant! Je me revois chanter La Mélodie du bonheur, en sortant du studio, dans la neige, sur le boulevard Saint Laurent, en marchant jusqu’à la rue Cherrier où j’habitais.

Cette pièce est marquante. Je ne suis pas prêt de l’oublier! Même si je ne l’ai pas dansée depuis un quart de siècle, ma mémoire demeure vive! Comme si, à 58 ans, j’étais un fossile qui a conservé les marques du langage chorégraphique de Zab : du regard au souffle, de l’enracinement aux subtilités de la circulation, du transfert de poids à la conscience de l’espace jusque dans les sphères de la vie! En effet, il ne s’agit pas simplement de danse et de mouvement car l’apprentissage de Zab Maboungou prend forme et perdure à travers différents aspects de la vie. Au cours de ma vie, j’ai suivi d’autres formations stimulantes et travaillé pour d’autres institutions, notamment l’Opéra Royal de Wallonie à Liège (Belgique), le Theater Aachen à Aix-la-Chapelle (Allemagne) et le théâtre du Capitole à Toulouse (France). Mais j’ai toujours ressenti le désir profond de revenir à Nyata Nyata me nourrir auprès de Zab Maboungou.

Dans mon cheminement de vie, je me considère comme un revenant. J’ai fait un lien à Mozongi quand je me suis envolé en Guadeloupe pour la première fois de ma vie, à 51 ans, avec les cendres de mon père sans connaître son histoire. Mon père qui a grandi en Guadeloupe est parti faire son service militaire obligatoire en métropole où il a rencontré ma mère à l’occasion d’un tournoi de football qui opposait un club de joueurs antillais à une équipe suisse. Après le match, c’est lors d’un bal et par la danse qu’ils se sont connus, aimés et mariés. À la mort de mon père, je me suis rendu dans sa ville natale, à Basse-Terre, et l’employée de l’état civil a constaté par mon livret de famille que nous avions le même grand-père! Mon père n’a pas été reconnu à sa naissance par son père qui a ensuite eu dix enfants avec une autre femme. Je porte ainsi le nom de famille de ma grand-mère paternelle originaire d’Inde, via la Dominique, qui était une colonie britannique.

Après le décès de mon père, j’ai rencontré une danseuse de 50 ans avec l’accent Suisse sur une plage de Fuerteventura et nous avons improvisé ensemble sur le sable. Par un incroyable concours de circonstance, il s’avère que cette dame était la sœur de la meilleure amie des deux sœurs chez qui mon frère et moi allions chaque année en vacances entre l’âge de six et neuf ans à la Chaux-de-Fonds, dans le canton de Neuchâtel! J’ai alors fait un lien avec Mozongi, comme si mon père me disait : « Continue de danser! ». Malgré mon âge, mon souhait le plus cher serait de prendre part, auprès des nouveaux interprètes de la compagnie Nyata Nyata, à la nouvelle version de Mozongi.

Like a prayer to my ancestors - Marion Landers (Mozongi dancer during its revival in 2001)

Mozongi isn’t just a piece, it is an entire training that approaches African dance in a resolutely different way to the one I’d learned from other companies, which were more focused on learning folkloric dances and contemporary choreography. Zab Maboungou’s is both a philosophical and historical approach to technical training. In this sense, Mozongi represented a new mode of dance training for me.

I studied ballet for ten years, then did a bachelor’s degree in contemporary dance in Vancouver. I was a good dancer, but my body didn’t fit the standards of ballet dance. These barriers disappeared when I started dancing for contemporary African dance companies. I then danced for seven years in Vancouver for a contemporary Afro-Brazilian company. It was a gift to work in an environment where everything that had previously been considered a disadvantage became an asset. Dancing for a professional company was a victory for me and for my family, who had invested in my dance education.

On the recommendation of a dancer from Quebec City, I sent an audition video to Nyata Nyata and was invited to dance Mozongi at Place des Arts. I arrived in Montreal in the fall of 1999. It was a completely immersive experience, as I was living with a friend of Zab’s family and working for the company’s touring agency. I worked all day for the agency and then, in the evening, I trained at Nyata Nyata. It was very difficult because we rehearsed in the evening from 7pm until after 11pm. I was young and had a lot of energy.

I have always had a good rhythm even in ballet, I love rhythmic combinations. The « tilly tilly tilly tintin tin! » is a movement phrase in which I excelled. You have to stand on your demi-pointes as if suspended by the upper body and at the same time work on your footwork while remaining in this posture for an eternity. This sequence requires a mixture of accuracy and relaxation. When you find the posture, it is magical. If not, it is real suffering! I really like the jump sequence because its rhythmic score is very sophisticated.

This piece is also a victory for me because I suffered from asthma. However, Mozongi requires the dancer to master and manage their breathing! I had to dance for 50 minutes continuously whereas in the companies I had danced for before, I would perform my parts and then get a rest off-stage while others danced their parts. With Nyata Nyata, I had to constantly sustain my energy and watch my breathing. Breathing is an important element in choreography because it will affect the movement if not managed properly. Zab’s technique teaches sequencing for the breath in accordance with each movement. This breathing technique is a gift that I still use continuously in my life.

Mozongi represents a challenge both physically and mentally. This piece requires a certain maturity because it is a work in which one must give oneself completely. It is not simply about executing movements prepared in advance. It is much more than that! It is about understanding dance on different levels: physical, philosophical, historical. Mozongi means « those who return » in Lingala. It asks the question: ‘Who are we in space and time and where are we returning from?’ I was 23 years old and I was probably too young to understand everything but I felt that this work was very important on a spiritual level. I carried a responsibility towards my African ancestry. I felt a deep connection with my ancestors in presenting this work. At the beginning of each performance, I prayed to my African, Indonesian and European ancestors to help me for an hour. If they could survive all that they had, then I could get through the piece! As soon as the show began, I remember us entering the stage, lying on the floor, in the dark, very gently, to begin the first movement “krati krati”. I still feel all the strength, anticipation, hope and inspiration contained in this tableau that resonated for me like a prayer.

Mozongi represents the affirmation of my African heritage. My father is from South Africa and my mother is Irish-Canadian. Both sides of my family have suffered histories of oppression. I danced for about ten years for three Afro-contemporary companies, two in Vancouver, one in Montreal, and I have choreographed in this style for over another ten years. Each “nyata”, each step I have taken towards my African heritage represents both surprise and pride for my South Africa family, who were traumatized by Apartheid.

What remains for me from Mozongi is a deep sense of knowing a technique. The finak undulations for me are a giant movement. This sequence contains the principles of all the previous movements with the feet. It is a movement that begins again and yet it is the end. This space allows one to reconnect with the earth. Zab Maboungou, Mozongi and Nyata Nyata represent a fundamental experience in my life for which I am deeply grateful.

Back in Vancouver, I began teaching contemporary African dance at the university. I created a class called “Introduction to African Dance Forms” based on the forms of expression I studied: Afro-Brazilian, West African dances, RIPADA (Zab Maboungou’s technique) and Afro-contemporary. I included elements of Mozongi in my class. For example, the moment of “krati krati” represents a specific groundwork that provides dancers with a technique to understand our relationship to the earth and the sky.

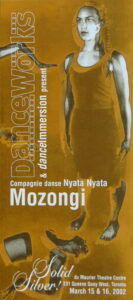

Programme du Festival Dance Immersion de Toronto, 2002 Avec Marion Landers en couverture

Trusting my intuition - Mona El Husseini

When I think of Mozongi, I think of Zab Maboungou and Nyata Nyata. I have never seen the show but I have taken classes with Zab. For me, they are not separate elements, they are superimposed. And they continue to modulate each other as I spend time rehearsing and learning with Zab the detail of the gestures, the process of refining the movement and the nuances of the rhythm. This aspect of rhythm in particular and the multidimensional way Zab teaches it is difficult for me because it is new. A moment of hesitation comes back again and again when I think I have understood something and can finally feel comfortable because I always discover a new layer to deepen.

This clarification of gestures intrigues me, because it is an aspect that I have wanted to work on for a long time. How can we observe the difference of each gesture? How can a slight difference change the weight and open up a completely different meaning? This work helps me to be comfortable with my independence in the sense that I feel I can trust my body, my timing and my intuition, despite my mind that tends to question them. The body is the only context where different elements can coexist and find balance. This idea of being both independent and in relation to others allows me to exist in space in an autonomous and singular way while connecting to the rhythm and presence of others.

There is something martial in Mozongi‘s score as in the presence. I trained a little in martial arts in Egypt and this coexistence of contrasts or oppositions occurs at the same time: strength and linearity coexist with softer and circular movements, at the same time. The “duck” sequence is one of my favorites because it juxtaposes a movement of force where the arms are angular, palms facing the body, then the hands soften, while retaining the power or the meaning of the gesture. In addition to its polyrhythm, this sequence operates a journey in space while composing music in silence.

Mozongi connects me to my past and, by extension, to my ancestors. I have a curious desire to know my ancestors in my personal creative work. I have gotten into the habit of questioning my mother and my living relatives about the ones who passed, whom I have not met. I am interested in finding ways to communicate with them, through the objects they used everyday, to get to know how they lived their lives.

The first time I came to Nyata Nyata, it was to participate in the Drums and Dances workshop. I instantly felt at home there. The feeling of warmth in the studio reminds me of Egypt where I lived and where I learned contemporary dance. It’s a literal warmth but also a metaphorical warmth in the people, the space, the teachers, the musicians and the dancers. I felt that affinity. And it was a relief to find a place that allowed me to access a familiarity that I don’t necessarily have access to here in Canada.

The walk is the hardest part for me. First of all, it’s the beginning of the piece and this walk corresponds to a moment where I feel I need to show myself: it’s the moment where I enter the stage. So for me, it’s the most vulnerable part of the piece, because I’m standing and, for some reason, when I’m standing, I feel less comfortable than when I’m close to the ground. Finally, this walk engages my own relationship to the rhythm of the drums and to that of other bodies. It is not different from what happens in my daily personal life. So that’s why it’s quite dense for me!

Mozongi‘s work increases my awareness because I have to be attentive to everything that’s happening, and many elements are playing out at the same time. The commitment to presence is really heightened and this hyper awareness disrupts my mind from wandering or being distracted. Whereas in other pieces that are not as physically engaging or where I do not need to be present in multidimensions, my mind begins to take over my body. This is not the case in Mozongi where my body takes precedence, as do intuition, a sense of timing and empathy.

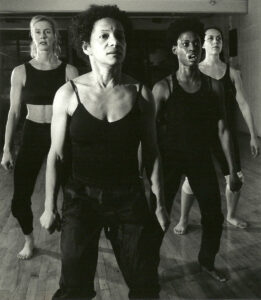

sur la photo : Mona El Husseini. Photographe : Carson Asmundson, 2024